Syrians started flowing to Türkiye at the outset of the Syrian civil war back in 2011. As their numbers were rising to nearly 4 million refugees, their presence started posing several challenges to the host country’s labour market. How to accommodate nearly a million workers concentrated in a few provinces, relatively unskilled, with limited Turkish language skills? The answer, partly, involved integrating them into sectors hungry for informal workers, such as the textile and clothing industry under harsh working conditions and informality. The situation of these refugees in the labour market has gradually improved. The government’s adoption of more flexible legislation, allowing refugees to be formally hired by companies since 2016, and the initiatives led by the ILO Office for Türkiye, including impactful programs like KIGEP, have played key roles.

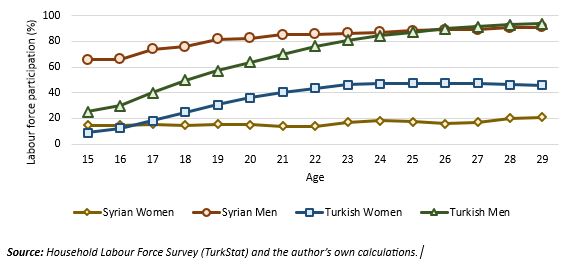

Figure 1. Labour force participation rates in Türkiye by age, 2016-2019

However, a persistent issue remains – the limited access of Syrian women to the Turkish labour market. As of 2022, the employment rate of Syrian women in Türkiye (15-64) was 19.6 percent; higher than the one Syrian women held in Syrian back in 2009, 10.1 percent, but still sensibly lower than the one held by Turkish women, 34.0 per cent. , it falls to 10.4 percent. The comparison with their Syrian male peers and Turkish male peers is also provided in Figure 1 for clarity.

Figure 2. Labour force status and NEET rates (in boxes) by age; female Syrian refugees

Source: Household Labour Force Survey (TurkStat) and the author’s own calculations.

The population of young female Syrian refugees is a vivid example of a group experiencing intersectional discrimination, making them one of the most vulnerable groups This vulnerability arises from a combination of factors: their refugee status, entailing restricted; limited proficiency in the local language; a lack of recognition of prior learning; weaker professional networks; gender-related and cultural challenges inherent to being women from a MENA country, including assuming responsibility for household duties and childcare; and their youth, characterized by a lack/reduced bargaining power and an increased propensity to employer abuse. In sum, an immense challenge.

Based on the three pillars of the refugee response program, what can be done about it? What have we learned anything during the years of refugee crisis in ?

Pillar 1: Improving skills and employability

Strong incentives must be provided for women to work, relying on quotas is wishful thinking. Programmes must actively encourage women’s participation by addressing their needs. In a recent on-the-job training programme, 23.0 percent of the applications came from Syrian women and 77.0 from Syrian men; mirroring their unemployment percentages of their share in unemployment; 20.5 percent of unemployed Syrians are women while 79.5 are men. If women do not have incentives to participate, simply offering jobs won’t suffice to increase their participation

Training programmes that provide stipends based on attendance, rather than on results may attract participants but they don’t necessarily cultivate successful job seekers. Some trainings and courses provide stipends to encourage Syrian women (and men) to attend. While this creates a seemingly "win-win situation," it is crucial to acknowledge that the provision of daily stipends often draws in professional stipend seekers organized in networks. These individuals collaborate, calling each other whenever an opportunity arises. Moreover, the absence of incentives to maximize their learning opportunities, such as performance stipends, hinders the effectiveness of these programmes.

Language skills and family attitudes matter, and these can be influenced by educational policies. A recent survey conducted by ILO Ankara focused on the labour market situation of young Syrians’ (18-29 years-old). Subsequent research delved into the impact of language skills on the likelihood of young Syrian women participating in the labour force. Having an intermediate level of Turkish is associated with a 19.7% increase in the probability of participation, while an advance command of the language yields a 27.8 %increase. Additionally, being born into a family where it is acceptable for a woman to work outside the house results in a 23.1% increase in the probability of working or seeking employment. These determinants can be positively influenced through policy measures, such as emphasizing women’s right to work or to accessing extracurricular language courses.

Pillar 2: Supporting job creation and entrepreneurship opportunities

Promote working from home as in intermediate step. Remote working might be a solution for some women who feel more comfortable working from home. Utilizing online platforms for training in AI applications, language teaching, and freelancing might work out well for part of the population with a minimum level of skills. The skills requirements are substantial, but some of them (internet banking, English language, financial literacy) can be acquired and would provide positive spillovers to the society not just to the individuals.

Pillar 3: Supporting labour market governance and compliance

Foster role models for the future. While women are no different from others at birth, some perceive that they can decide their future path while others believe that certain opportunities are not meant for them. Syrian women in Türkiye seem to lack role models that act as trailblazers or trendsetters. Creating such models involves identifying talented individuals, promoting their growth and supporting their attendance to elite universities[4] to showcase their capabilities.[5]

Conclusions

In conclusion, a combination of employing the right incentives, investing in future generations and harnessing the potential of technological advancements to help current working-age women appears to be a sensible approach. While it is acknowledged that these ideas/initiatives may not lead to a large influx of young Syrian refugee women into the labour market, they do hold the potential to set progress on the right track.

[1] See article at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7068284/.

[2] See https://www.ilo.org/ankara/areas-of-work/employment-promotion/WCMS_836438/lang--tr/index.htm for information regarding an otherwise successful programme (in terms of skill creation).

[3] The research «The Youth and COVID-19: Access to Decent Jobs amid the Pandemic»

was funded by the US Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM). https://www.ilo.org/ankara/news/WCMS_849564/lang--en/index.htm

[4] See this initiative, https://react.mit.edu/.

[5] See other recommendations at https://www.orange.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/women-access-to-labour-market-Syria-EN.pd

Acknowledgement: The research has been funded by BPRM, Bureau of Populations, Refugees and Migration of the United States of America.

Article