Almost to the day one year ago, the Global Initiative on Decent Jobs for Youth brought together youth employment representatives and experts during its annual conference in Rome, Italy. Under the tagline “Rights and Voices of Youth”, we reflected together on the transformative power of collective action in advancing a rights-based and inclusive youth employment agenda.

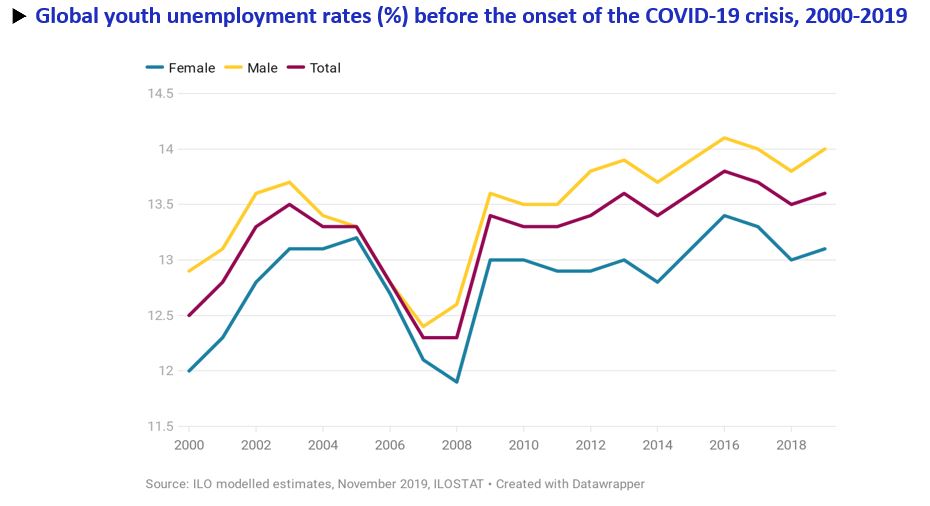

With the COVID-19 pandemic and the worst ever economic and labour market downturn in most of our lifetimes, we are at great risk of damaging the labour market prospects of young people. Young workers were already vulnerable and often excluded from labour markets before the current crisis. Persistently high youth unemployment rates, 13.6 per cent in 2019, are around three times the level of adult unemployment rates.[1] Brief periods of unemployment during a young person’s early labour market experiences are not unusual. But the serious risk of persistent increases in long-term unemployment is likely to have life-long scarring effects on the individual’s employment prospects and wages.

Amplified vulnerabilities of the youth workforce threaten in particular low-paid young workers and young women. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, over 328 million of the world’s young workers were in informal jobs, three in four young workers globally, and did not have access to social protection. As of 2019, an additional 267 million youth (aged 15-24) were not in employment, education or training.[2] Among these “NEET”, women outnumbered young men two to one. Young people are also increasingly in less secure forms of employment, such as temporary and part-time and agency work.[3]

Young women in the world of work are especially vulnerable. Before the outbreak, young women spent almost three times as much time on unpaid care and domestic work than young men. Widespread closures of schools and the unavailability of affordable childcare services are intensifying the double burden of care often borne by young women, while they are also in the frontline as care workers fighting this pandemic.

Young people are confronted with the disruption to education, training and work-based learning. The near 496 million young people who were in education before the pandemic, are now experiencing significant learning disruptions. Young people who are forced to quit or delay their studies will face lifelong earning losses. As a result, transition into productive employment and decent work is much more arduous for young labour market entrants.

The situation is going to get much worse. A new global survey by the ILO and partners of the Global Initiative on Decent Jobs for Youth reveals that over one in six young people (aged 18 to 29) surveyed have stopped working since the onset of the COVID‑19 crisis.

Against this dire backdrop, the world needs to act collectively and decisively. The key messages from last year’s gathering of the Global Initiative on Decent Jobs for Youth are as pertinent as ever: promoting youth rights at work and strengthening their voices in the world of work are key to achieving a future with decent work for all. We need to ensure investments in youth employment and address the specific needs of disadvantaged youth groups, including young women, young people with disabilities and young migrants and refugees.

To prevent a generation of young people being harmed by the crisis, the ILO calls for immediate, large-scale and targeted action:

As the recovery phase commences across the globe, economic and employment policies, particularly fiscal policy, need to support young people’s (re-) entry to education, training or employment. These measures need to benefit especially those belonging to the hardest-hit groups as the crisis will have long-term impacts. Policies need to be complemented with investments in growth sectors with the capacity to absorb the youth labour force, such as renewable energies and digital technologies, among others.

Strengthened national employment policies will support youth-led enterprises and young workers to build back better. Existing national employment policies need updating including co-ordinating the transition from immediate response measures to an integrated employment promotion framework over the long-term. There is much to learn here from the European Union’s Youth Guarantee, which served as a counter-cyclical active labour market measure in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and these employment guarantees can also be designed for developing and emerging countries to match their contexts.

Targeted support to enhance youth skills can raise productivity and counter reduced labour demand. Taking full advantage of online learning and training requires better broadband connectivity and investments in ICT equipment, along with quality curricula tailored to a virtual audience

Young people’s access to social protection and unemployment benefits needs to be extended. Cash transfers need to reach young people in the informal economy, potentially through digital platforms that can rapidly reach those most in need. Relaxing social, health and unemployment benefits eligibility requirements can be coupled with coaching and job search support that help young people with little experience in navigating the labour market. Portability of social protection for young migrant workers is critical.

Youth-targeted wage subsidy programmes and work sharing arrangements protect young workers. After containment measures have been lifted, wage subsidies reduce the costs of retaining, hiring and training youth. Wage subsidies have proven to be effective in increasing long-term employment prospects for youth. Expansions of wage subsidies and work sharing schemes (subsidized reductions in working hours) should also provide access to all young workers, regardless of the type of employment contract.

Expanding support to youth-led micro, small and medium enterprises protects jobs in the short-run and spurs innovation during the recovery period. In the short-term, lending to young entrepreneurs and youth cooperatives should be combined with access to business development services and coaching so as to ensure that businesses withstand the crisis. During the recovery phase young entrepreneurs and innovators are in a unique position to exploit new opportunities in emerging sectors through start-ups.

Concerted efforts are needed to protect young people in essential occupations, such as health and care workers, along with those who enter the labour market or return to work as workplace closures are lifted. Work-related ergonomic and psychosocial risks associated with the pandemic, disproportionately impact young workers, especially young women facing an increased unpaid care load. Appropriate control measures need to be adapted to young people, including their training and appropriate personal protective equipment. Ensuring the right to disconnect in the current context of teleworking is also important for young workers.

Social dialogue is critical in mitigating the negative effect of COVID-19 on young workers, covering such issues as cuts to working hours, partial employment, apprenticeships and internships during the pandemic. This includes maintaining the rights of young workers and enhancing the capacity of workers and employers organizations to represent them, especially those in the informal economy, rural economy, migrant young workers and young digital platform workers. There is a very real possibility that the trend towards temporary and other less protected forms of work amongst young people, will become entrenched as a consequence of the pandemic. Promotion of freedom of association and effective social dialogue is crucial to protect and improve the basic employment rights of young people along with productivity as part of an effective response to the COVID-19 induced economic crisis.

The COVID-19 crisis is threatening to exacerbate the exclusion of young people for years to come. Based on social dialogue, we advocate for an integrated crisis response that supports incomes, promotes decent work, stimulates demand, as well as protects and extends rights at work. These are crucial political choices that will shape the future of our youth, our economies and societies for years and decades to come.

By Sukti Dasgupta, Chief, Employment and Labour Market Policies Branch, ILO

The ILO Policy Brief Preventing exclusion from the labour market: Tackling the COVID-19 youth employment crisis as well as the ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work (4th edition) provide more information about youth labour market vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic and discuss policy responses.

This article is part of the Decent Jobs for Youth Blog Series: Youth Rights & Voices. The Blog Series highlights the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young women and men in the world of work and discusses action-oriented policy responses and solutions. If you would like to comment or contribute, please contact decentjobsforyouth@ilo.org.

[1] ILO (2020): Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020

[2] ibid.

[3] ILO (2017): Global Employment Trends for Youth 2017, Chapter 5

Article

Global

Global