Crises fall hardest on the most vulnerable. Young people make up one such group, particularly when it comes to the social and economic impact of the virus pandemic.

Making the transition into decent employment is a tough challenge for young people, even in the best economic times. Figures from 2019 from the ILO – before the virus outbreak – demonstrate this, with one-in-five of those aged 15 to 24 (equivalent to 267 million young people worldwide) classified as NEET, or not in employment, education or training. Even during economic upswings, young people that enter the labour market face significant challenges: jobs that do not match their education, outdated skills that do not address the labour demand, and a lack of knowledge on where and how to look for jobs. The ILO estimates that the expected global economic recession will destroy millions of jobs, comparable or above the impact of the global economic and financial crisis when youth unemployment alone rose from 73 to 81 million between 2007 and 2009 (ILO Monitor 2nd edition: COVID-19 and the world of work Updated estimates and analysis.

There are five reasons why young women and men will be particularly affected by the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic.

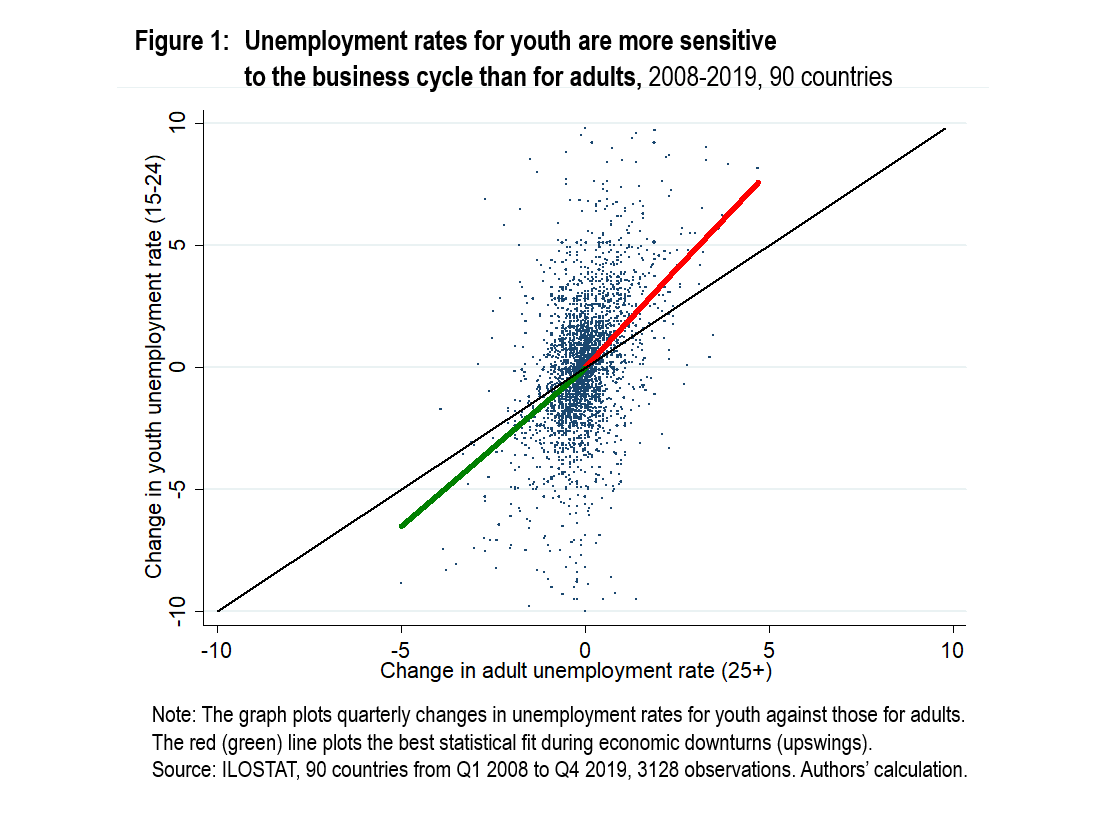

First, young workers are affected more than their older, more experienced colleagues by recessions. Experience shows that younger workers are often the first to have their hours cut or be laid off. In fact, since 2008, economic downturns have led much faster increases in the youth unemployment rate compared to the rate for adults (as shown in figure 1, based on a global analysis of 90 countries from 2008 to 2019). Furthermore, a lack of networks and experience can make it more difficult for them to find other, decent jobs and they can be pushed into work with less social and legal protection. Young entrepreneurs and youth cooperatives face similar problems because a tight economic situation can make it harder to find resources and financing, and they lack the know-how to cope with difficult business and supply chain conditions. There is little to suspect that the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will be easier to navigate for young people. On the contrary, movement restrictions and the substantive reduction in business activities will make it hard for young workers, entrepreneurs and jobseekers to find or sustain their employment.

Second, three in four young people work in the informal economy, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, for example, in agriculture or in small cafes and restaurants. Young people making ends meet by selling tea in a roadside shop or being employed as daily wage-earners in the agricultural sector cannot work from home. As both their health and livelihoods are at stake, young people, many with little or no savings, will need to continue working to stay afloat.

Third, many young workers are in “non-standard forms of employment”, such as part-time, temporary or ‘gig’ work. Such jobs are often low paid, with irregular hours, poor job security, and little or no social protection (paid leave, pensions, sick leave, etc). Importantly, these jobs often do not provide adequate medical insurance coverage. Young workers that the current pandemic has pushed out of jobs often cannot access unemployment benefits due to an insufficiently long contribution period. For others, the labour market institutions, such as job-centres, that could provide some sort of safety net are already beyond capacity and ineffective.

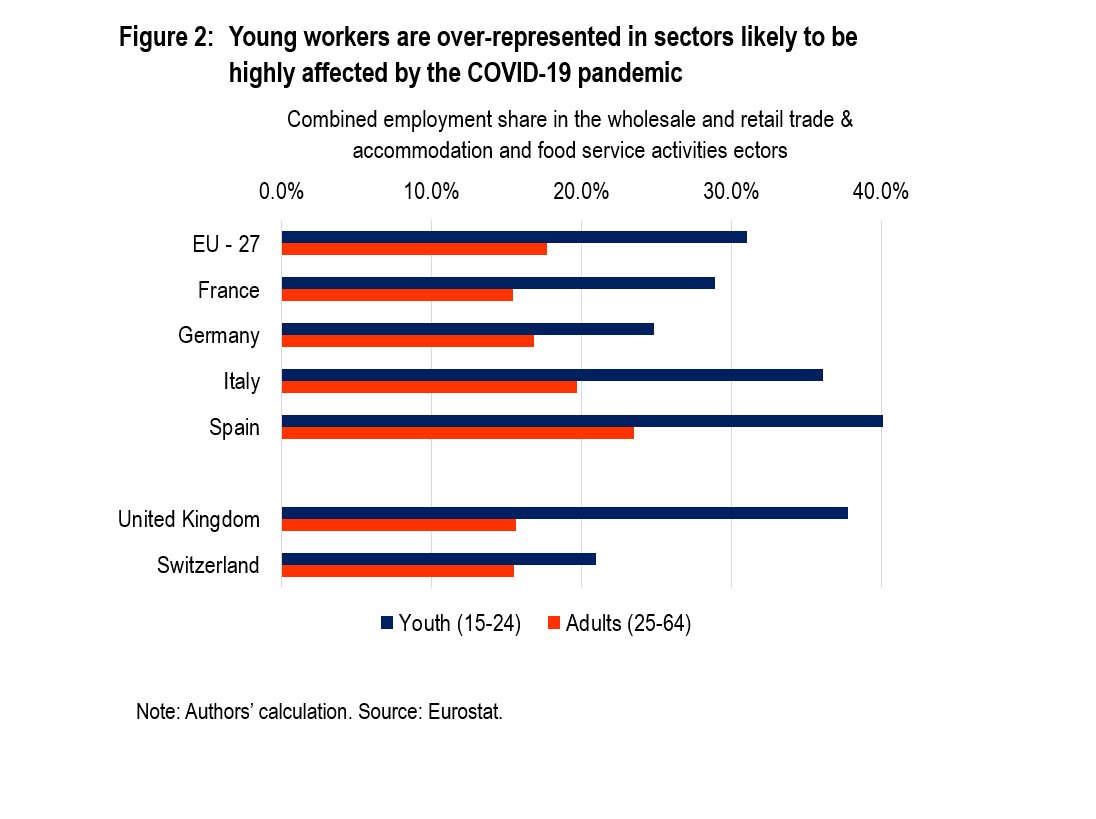

Fourth, young people commonly work in sectors and industries that are particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2018, roughly one-in-three young workers in European Union member states were in the wholesale, retail, accommodation and food sectors (as shop assistants, chefs, waiters, etc., see figure 2). These sectors are predicted to be among the businesses worst affected by COVID-19 as in many countries, authorities have instituted social distancing measures, made home confinement an obligation and/or closed restaurants, hotels and shops, with the risk that many will go out of business permanently. Young women, in particular, are likely to be affected because they make up more than half of youth ’s employed in these sectors – for example, women account for 57 per cent of young people in the food services and accommodation sector in Switzerland and 65 per cent of those in the United Kingdom.

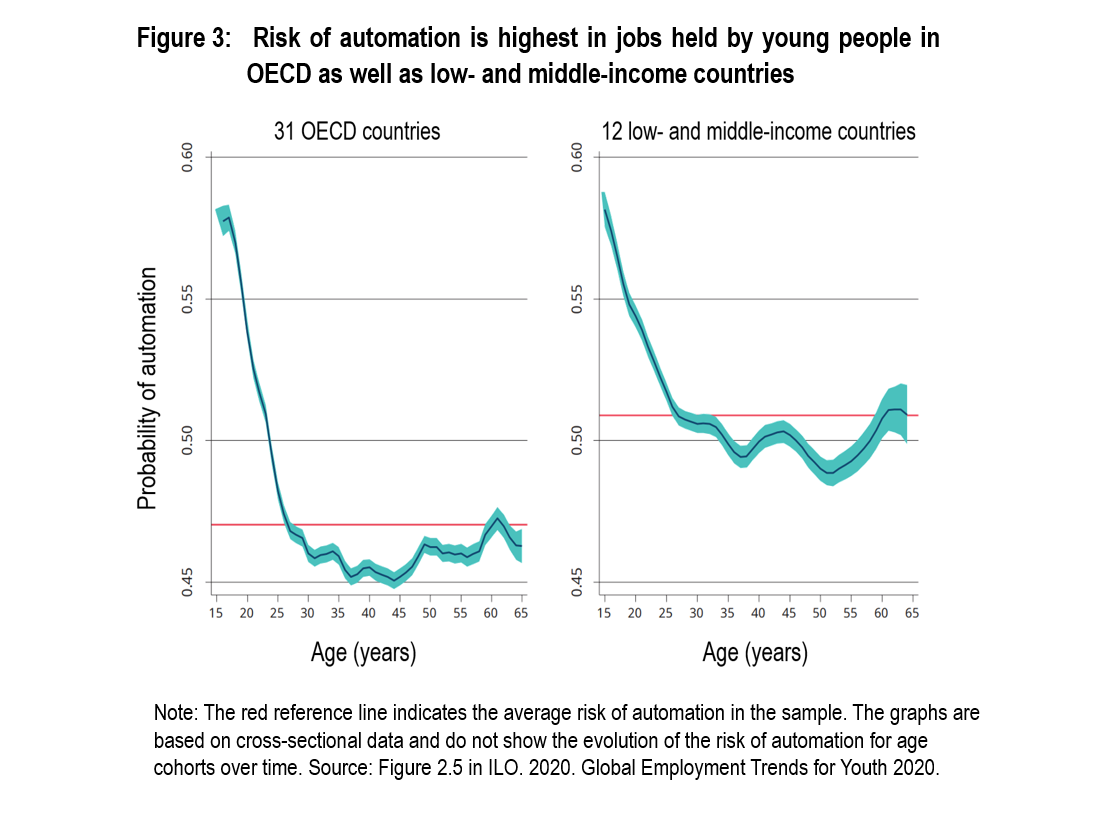

Fifth, young people are more at risk than any other age group from automation. The ILO, in its recently published report Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020 highlights that the risk of automation peaks among young workers, as they are more likely to be in more automatable occupations. Moreover, within the same occupation, the entry-level jobs held by young people tend to have a greater proportion of automatable tasks (figure 3).

So, while the COVID-19 emergency is going to affect almost everyone in the world, regardless of age, income or country, young people are likely to feel the pinch harder. Therefore, when world leaders draw up support and stimulus packages, they need to include special measures to help young people, and ensure they are included in support schemes – whether they are employees, entrepreneurs or jobseekers. Youth losing their jobs, including those previously in diverse, less protected forms of employment, should be able to benefit from income support schemes, such as cash payments and other short-term measures. Likewise, access to emergency relief grants and increased flexibility of loans for businesses needs to be ensured for young entrepreneurs.

It isn’t just individuals who are damaged by increases in youth unemployment, it exerts a great and long-term cost on our societies too. Entering the labour market in a recession can lead to significant and persistent earnings losses for young people that can last their entire career. Ignoring the particular problems of young workers risks wasting talent, education and training, meaning that the legacy of the coronavirus outbreak could last for decades.

by Kee Kim (ILO) and Susana Puerto (ILO)

This article is an extended version of a post published on the ILO blog “Work in Progress”. With it, we are launching the Decent Jobs for Youth Blog Series: Youth Rights & Voices. The Blog Series highlights the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young women and men in the world of work and discusses action-oriented policy responses and solutions. The blog will feature contributions of youth representatives, youth employment experts and Decent Jobs for Youth partners. If you would like to comment or contribute, please contact decentjobsforyouth@ilo.org.

To bring youth voices to the forefront of action and policy responses, the Global Initiative on Decent Jobs for Youth (DJY) and its partners are conducting a survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth rights. Participate in the survey now!

Article