The informal economy in Brazil, like in other Latin American countries, represents a significant share of employment and income to young people. It has also contributed to the recovery from the shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, with informal employment accounting for 43 per cent of the number of jobs gained (jobs created minus jobs lost) in Brazil between the third quarters of 2020 and 2022 (ILO, 2023).

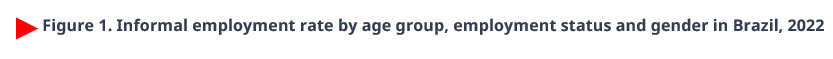

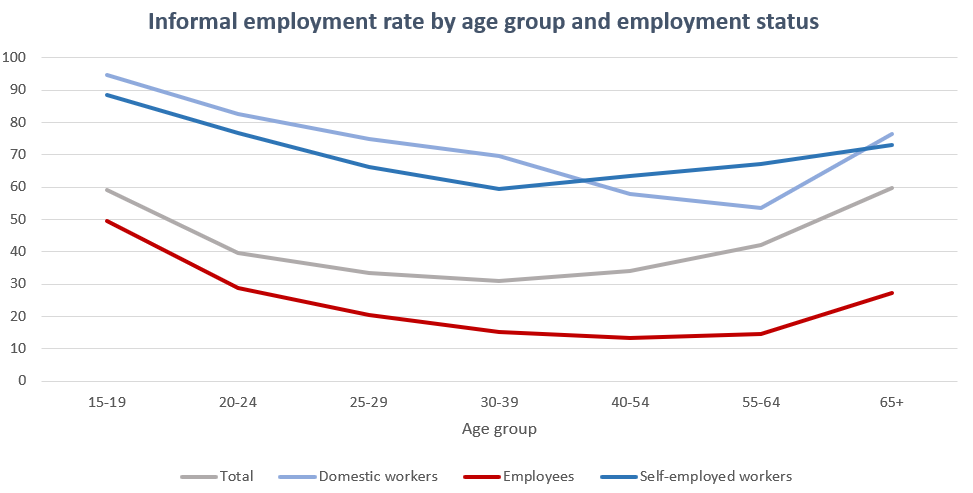

As the figure below shows, the share of informal employment in total employment in Brazil tends to follow a U-shape curve, which means informality is concentrated among youth entering the labour market: 59 per cent among young people aged 15-19, 40 per cent for those between 20-24, and 34 per cent among youth aged 25-29. It reaches its lowest point among adults aged 30-39 (31 per cent), and it increases again for older workers. The high share of young informal workers is explained by the fact that in the absence of productive, formal jobs, informality is often the entry to the labour market (ILO, 2023), particularly among young people from low-income households and those lacking skills, work experience, or productive assets (Chacaltana et al., 2019). A look at the employment status of young people also shows the high levels of informality among young domestic workers[1] and those in self-employment[2], which illustrates the strong connection between informality and vulnerable employment. Additionally, it is observed that young men are slightly more likely to be in informal employment than young women.

The informal economy also presents many risks to workers, firms, and society at large. Informal workers are associated with worse work prospects (especially to young workers who start their professional careers in the informal economy), low and volatile income, vulnerable working conditions, low-productivity jobs, and lack of social protection. Informal firms, on the other hand, face challenges in accessing financial and production resources as well as government support packages, which hinder access to markets and growth. These risks have many undesired effects on society, in which a large informal economy reduces the State’s capacity to invest in productive resources and social programmes, increases poverty and inequality in many forms, and creates a fractioned society (Salazar-Xirinachs & Chacaltana, 2018).

The ILO Recommendation 204 (ILO, 2015) advocates for promoting the transition from the informal to the formal economy as a strategic step towards boosting a more dynamic business environment and productive and decent employment for all, especially young people. In this context, Brazil’s “Workers Protection Programme” (PPT) offers an interesting example of an intervention aimed at boosting productivity and formalizing informal workers.

The programme implementation is carried out by the local government of Maricá, situated in the metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro. It offers two types of benefits to incentivize formalization among informal workers, including those in self-employment and who live and carry out their economic activities in the region. First, the “Production Stimulus Benefit” (BEP) will pay half minimum wage to programme beneficiaries for use in their economic activities. Second, the “Cota10 Benefit” will serve as a savings account for programme beneficiaries and rely on monthly payments made by the local government equal to 10 per cent of the declared earnings derived from the beneficiaries’ work activities. Beneficiaries will be able to use this savings account under certain conditions, such as childbirth, sickness, drop in revenue of at least 50 per cent, or as collaterals to access credit for their economic activities.

The programme is currently enrolling participants and is expected to start paying the benefits in April 2023. To participate in the programme, informal workers need to become formal by registering as an individual micro-entrepreneur (MEI) or becoming a cooperative self-employed worker (that is, joining an association of workers within the same sector). Then, the newly formal workers can register to become a beneficiary of the PPT, in which they will need to prove they have been carrying out their professional activities for at least three months and live in the Maricá region. Other relevant design features are the use of the region’s social currency, called “Mumbuca”, for the payment of benefits (Gama & Costa, 2021); the government’s awareness campaign on the importance of formalization; and the annual proof of beneficiaries’ participation in skills development programmes.

So, do such comprehensive efforts to boost formalization work?

Many studies have shown that positive effects on formalization originate from a set of policy instruments to boost inclusive economic growth, improve and simplify regulations, generate incentives, create awareness, and improve enforcement (Berg, 2011; Bertranou et al., 2013; ILO, 2014; Chacaltana, 2017; Maurizio & Vásquez, 2019). Similarly, though limited, there is evidence about the positive effect of active labour market policies (skills development programmes, entrepreneurship promotion, employment services, subsidized employment, and public works) on formalization outcomes among young people, a group that requires comprehensive measures to facilitate the transition to stable and satisfactory jobs (Escudero et al., 2019).

There is little evidence on monetary incentives paid directly to workers to boost formalization. However, a recent experiment carried out in Mexico provides evidence to the impact of monetary incentives on formal employment, especially among youth. Abel et al. (2022) tested a temporary wage incentive designed to encourage Mexican secondary school graduates to obtain and stay in formal employment. Their main argument is that young jobseekers in Mexico may be misled by higher entry-level wages in the informal than in the formal economy, when in fact the pattern reverses over time. For example, formal wages in their sample grow by about 25 to 35 per cent over the first six to twelve months of employment (driven by the acquisition of skills both at work and through training), while informal wages remain relatively constant. Therefore, the experiment offered a temporary (up to six months) formal employment benefit paid directly to young workers that amounted to nearly 20 per cent of the average formal entry level wage, hence addressing the above-mentioned wage gap between formal and informal employment, i.e., the misjudgement of young workers.

Abel et al. (2022) provides very positive results. The formal employment benefit had large employment effects in the formal economy (mainly coming from a reduction in informality), increased the likelihood of young people transitioning to a permanent contract, and did not lead to undesired consequences on young people’s decisions to leave school.

The programmes in Brazil and Mexico have some significant differences. In Mexico, wage incentives are given to encourage young workers to work in the formal economy. Meanwhile, in Brazil, self-employed workers are encouraged to register as formal micro-entrepreneurs so they can enjoy the benefits provided by the programme. Although there are some similarities regarding the informal economies of the two countries (ILO, 2021b), it is unclear whether Abel et al.’s (2022) argument about higher entry-level wages in the informal economy applies to Brazil. Despite this, both programmes share an innovative approach of using monetary incentives paid directly to workers to facilitate their transition and retain them into the formal economy.

Given such positive experience in Mexico, it is worth monitoring the implementation and results of the “Workers Protection Programme” in Brazil, considering its potential for replication and upscale. Finetuning programme costs and designing effective complementary interventions, such as promotion campaigns, skills development interventions, simplifying access to credit, and combining it with job creation strategies will be key to retain workers in the formal economy and avoid negative externalities.

In any case, it is significant to see this type of programmes being tested and implemented, especially those that target or include young people. Youth is a group that requires special attention since they face many difficulties to transition to a decent job, and their initial transitions into the labour market may leave long lasting effects in their life course.

[1] Domestic workers are paid employees who perform work in or for a private household or households (ILO, 2021a). The group of “Employees” includes private and public sector employees.

[2] Self-employment includes employers (self-employed workers who have employees working for them in their business) and own-account workers (self-employed workers who do not have any employees) (ILO, 1993).

References

Abel, Martin; Carranza, Eliana; Geronimo, Kimberly Jean; Ortega Hesles, Maria Elena. Can Temporary Wage Incentives Increase Formal Employment? Experimental Evidence from Mexico (English). Policy Research working paper; no. WPS 10234 Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Berg, J. (2011). Laws or Luck? Understanding Rising Formality in Brazil in the 2000s. Regulating for Decent Work, 123–150. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230307834_5

Bertranou, F. Casanova, L. & Sarabia, M. (2013). Dónde, cómo y por qué se redujo la informalidad laboral en Argentina durante el período 2003-2012. Research Papers in Economics.

Chacaltana, J. (2017). Peru, 2002-2012: Growth, structural change and formalization. CEPAL Review, 2016(119), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.18356/78b19d57-en

Chacaltana, J., Bonnet, F., & Leung, V. (2019). The Youth Transition to Formality. In https://www.ilo.org/global/docs/WCMS_734262/lang--en/index.htm. International Labour Organization.

Escudero, V., Kluve, J., López Mourelo, E., & Pignatti, C. (2019). Active Labour Market Programmes in Latin America and the Caribbean: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis.

Gama, A., & Costa, R. (2021). The increasing circulation of the Mumbuca social currency in Maricá, 2018-2020. Center for Studies on Inequality and Development (CEDE).

International Labour Organization [ILO]. (1993). Resolution concerning the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE): Fifteenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians. International Labour Organization.

International Labour Organization [ILO]. (2014). Recent experiences of formalization in Latin America and the Caribbean. International Labour Organization.

International Labour Organization [ILO]. (2015). In International Labour Conference, Recommendation concerning the transition from the informal to the formal economy. https://www.ilo.org/ilc/ILCSessions/previous-sessions/104/texts-adopted/WCMS_377774/lang--en/index.htm

International Labour Organization [ILO]. (2021a). Making decent work a reality for domestic workers: Progress and prospects ten years after the adoption of the Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189).In https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/domestic-workers/publications/WCMS_802551/lang--en/index.htm. International Labour Organization.

International Labour Organization [ILO]. (2021b). Employment and informality in Latin America and the Caribbean: an insufficient and unequal recovery: Labour Overview Series Latin America and the Caribbean 2021. International Labour Organization.

International Labour Organization [ILO]. (2023). PANORAMA LABORAL 2022: América Latina y el Caribe. In https://www.ilo.org/americas/publicaciones/WCMS_867497/lang--en/index.htm. International Labour Organization.

Maurizio, R. & Vásquez, G. (2019). Formal salaried employment generation and transition to formality in developing countries. The case of Latin America. Research Papers in Economics.

Salazar-Xirinachs, J. M. & Chacaltana, J. (Eds.). (2018). Políticas de Formalización en América Latina: Avances y Desafíos (1st ed.). International Labour Organization.

Article